Berrak zihinler için yalın, zengin, bağımsız bir Türkçe dijital medya üyeliği.

Ücretsiz Kaydol →

Rana Mengü

Editor @ Aposto

Lüksün tarihe saygısı: Raffles Londra

Londra’da Dior tasarımlı bir pavyon ve dahası.

Havaalanında güvenlik kontrolü sırası rezerve edilebilecek

Havaalanında beklemeye son veriliyor.

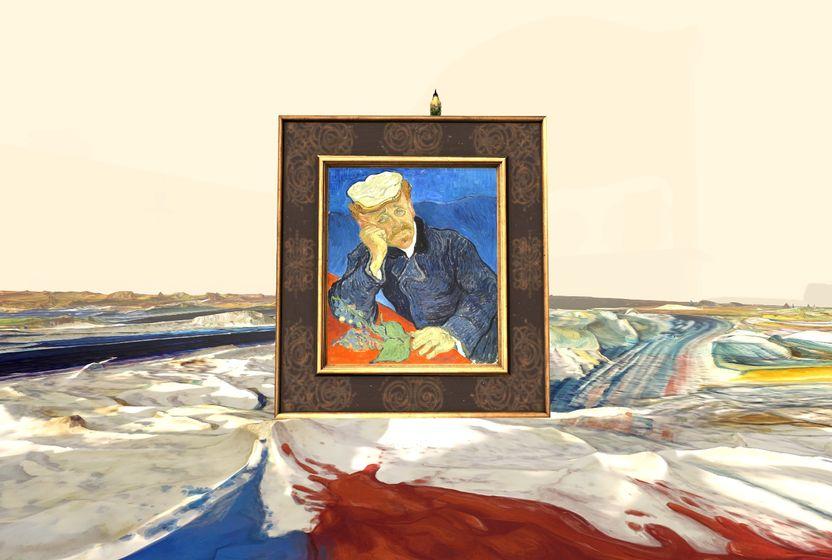

20 yıl sonra tekrar bir arada: Yamamoto ve Vadukul

Moda ve fotoğraf simdi de New York ve Paris’te ziyaretçileriyle buluşuyor.

Müze mimarlara karşı

Müze, pavyonun açılmadan önce masraflı onarımlar gerektirdiğini iddia ediyor.

Avrupa'nın en küçük şapeli, büyük bir aşkın kanıtı

Costello Anıt Şapeli ve kısa hikâyesi.

Depremden sonra Fas turizmini toparlayabilir mi?

Yıkıma karşı yeniden kurulanlar ve dahası.

Sharapova Aman New York’ta

Bir tenisçi, bir otel ve herkesi buluşturan bir inziva.